Electron

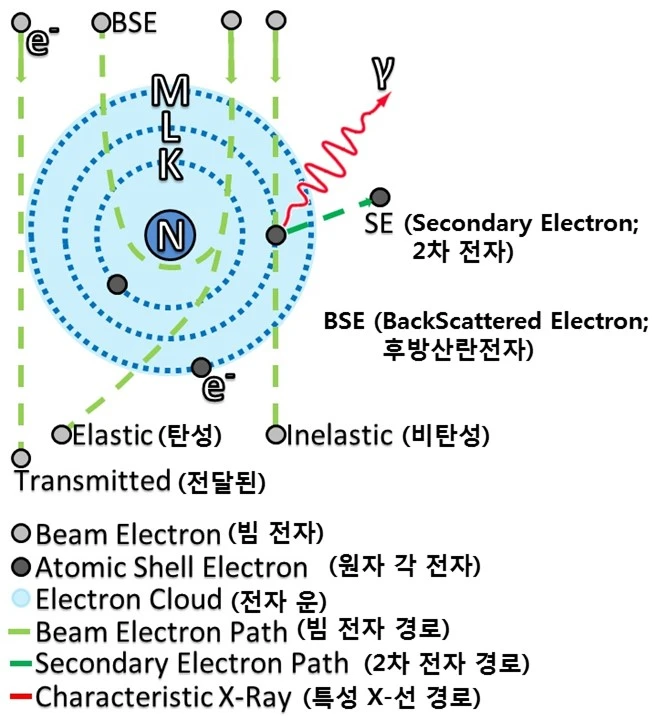

Incident electrons carry negative charge and interact with bound electrons and atomic nuclei in materials via the Coulomb force. Through these interactions, the electron’s path can be deflected; energy may be deposited as excitation or ionization; and in some cases photons are emitted.

Electron-Electron Interaction

Because both particles are negatively charged, a strong repulsive (Coulomb) force acts when an incident electron approaches a bound electron. This deflects the incoming electron, while the target electron generally remains bound unless sufficient energy is transferred.

The incident electron can excite the target electron to a higher energy level or ionize it. If an inner-shell electron is ejected, a vacancy is created and subsequently filled by an outer electron, often emitting characteristic radiation during de-excitation. In low-Z materials this may appear in the visible/UV range; in higher-Z materials, X-ray emission is more likely.

If the ejected electron retains enough kinetic energy to cause further ionization, it becomes a secondary energetic electron-commonly called a delta ray.

Electron-Nucleus Interaction

As a negatively charged electron passes near a positively charged nucleus, it experiences an attractive force that slows and deflects it. Because the nucleus (and thus the atom) is much more massive, its motion is usually small.

If sufficient energy is transferred to an atom, it can be displaced from its lattice site, producing Displacement Damage.

However, for most energies relevant to electronics, ionization is the dominant energy-loss process.

When an electron is rapidly decelerated in the nuclear field, it can emit a photon-bremsstrahlung (“braking radiation”). The closer the approach, the greater the deceleration and the higher the photon energy. Bremsstrahlung forms a continuous spectrum whose upper cutoff is the kinetic energy of the incident electron.

Electron Scattering

Image source: Electron-beam interaction and transmission with sample - Wikimedia Commons

Author: Zephyris / CC BY-SA 3.0

Most semiconductor devices are enclosed in opaque packages (plastic, ceramic, metal, etc.), so incident electrons typically need energies on the order of a few hundred keV or more to penetrate the package and reach the die.

In industrial and medical applications, beta particles from electron beams or radioactive sources often span ~0.01-4 MeV; such electrons can penetrate outer layers and affect internal circuitry.

At ground level, the flux of high-energy electrons is generally too low to dominate semiconductor reliability concerns. In space-especially within the Van Allen Radiation Belts-electron fluxes are much higher. Electrons in the ~0.1-10 MeV range are common and can readily penetrate packaging, contributing to effects such as Total Ionizing Dose (TID).

Related Articles

- Energy Transfer Mechanisms of Protons and Neutrons

- Energy Transfer Mechanisms of Photons

- Korean Radiation Test Facilities

- Energy Transfer Mechanisms of Ions

- How Was SEU Discovered? A Historical Insight into Radiation-Induced Failures in Electronic Circuits

- What is a Heavy-Ion Beam?

- Overview of Key Simulators for Radiation Effects Evaluation in Semiconductors