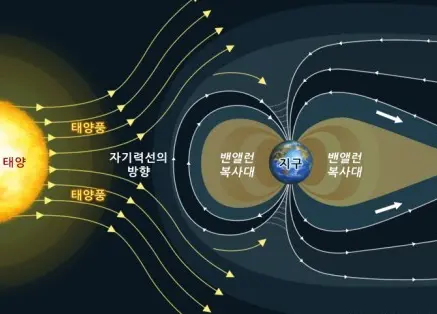

When charged particles from space are trapped in Earth’s magnetosphere-in the Van Allen radiation belts-they spiral along magnetic field lines and bounce (mirror) between the poles. Positively and negatively charged particles drift sideways (azimuthally) in opposite directions, slowly moving forward or backward (longitudinally).

This drift, together with the offset and tilt of Earth’s magnetic dipole, produces an asymmetric field that is comparatively weak over the South Atlantic, creating the South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA)-a region particularly problematic for satellites and missions in Low Earth Orbit (LEO).

The Van Allen belts consist mainly of electrons in the outer belt, and protons with electrons in the inner belt.

Space-weather conditions, orbital altitude, and shielding design strongly influence the radiation environment encountered by spacecraft. Dose can also vary across components depending on their location within the satellite and the surrounding materials.

Van Allen Radiation Belt

The Van Allen radiation belts are donut-shaped (toroidal) regions of high-energy charged particles trapped by Earth’s magnetic field, extending to roughly 10 Earth radii. They were first identified in 1958 with the launch of the United States’ first satellite, Explorer 1. Subsequent missions-culminating in the Van Allen Probes (launched in 2012)-have even observed a third, temporary belt forming under certain conditions.

Van Allen Radiation Belts

Source: Doopedia

The belts are named after Dr. James Van Allen of the University of Iowa. His radiation-detection package-featuring a Geiger counter and tape recorder-flew on Explorer 1, launched on January 31, 1958. Follow-on missions such as Explorer 3, Explorer 4, and Pioneer 3 confirmed the belts and helped characterize their structure.

Although the term “Van Allen belts” refers specifically to Earth, analogous radiation belts have been observed around other magnetized planets such as Jupiter and Saturn.